Though it’s remembered as a sweeping novel of the Civil War, the Civil War does not make up the majority of Gone With the Wind’s plot. More than half of the novel takes place during Reconstruction, the period directly after the Civil War. Mitchell provides a great deal of background information on Reconstruction. Yet very little of her history holds up to today’s factual standards. Nevertheless, it was acceptable to many scholars in her own time.

In this Story

Fooled by the Freedman's Bureau? Attempts to Explain Freedpeople's Politics

Justifying the Ku Klux Klan: Blending Romanticism and Historical Inaccuracies

Melodrama and Reconstruction: Exaggerations to Justify Jim Crow

Splitting From the Source Material: Margaret Mitchell's Editorial Choices

When we say scholars in Margaret Mitchell’s period (1900-1949) the group that most shaped her opinion of Reconstruction was the Dunning School. Not a formal institute or building, its advocates were part of a school of thought about the interpretation of Reconstruction. Established at Columbia University in the 1880s through the writings of William Archibald Dunning, a scholar from New Jersey, the Dunning School was one of the first academic groups in the country to study Reconstruction as an historic event.1 They were also some of the first scholars in the United States to study history the way we do today—by analyzing primary sources and making arguments about them.2 This makes the Dunningites (as they were known) very complicated. Because, despite the fact they were respected scholars who advanced their field, many of their arguments were fundamentally flawed when it came to their analysis of Reconstruction.

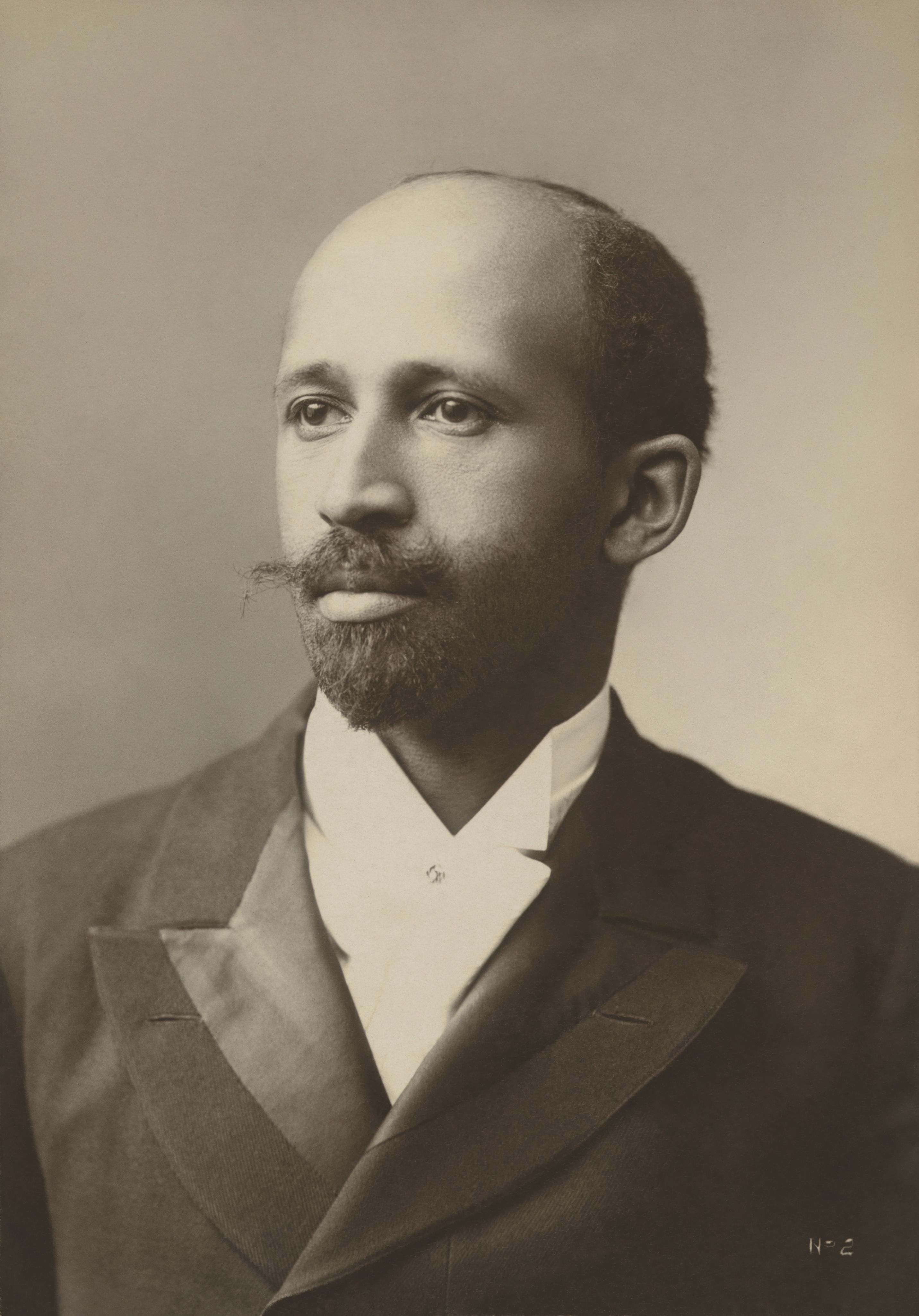

Dunning correctly argued that the Civil War was fought over slavery, that the Confederate states seceded illegally, and that because of their role in starting such a destructive conflict, the states that were part of the Confederacy deserved to lose some privileges as they rejoined the United States government. Dunning also argued that Reconstruction, the actual requirement for the Confederate states’ return to the US Congress, was a complete failure; primarily because the policies gave political and civil rights to Black people.3 Very few people criticized Dunning’s work during his lifetime. The important exception was prominent Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, who first began to counter Dunning in 1901. Dunning, like most white Americans at his time, believed that Black Americans were incapable of handling such rights, and that in granting them those rights, the US government failed “inferior” Black people and unreasonably penalized white Southerners by forcing them to acknowledge their former slaves as equals before they were ready to do so.4

1 John Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction, (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2013), 4.

2 Smith and Lowery, The Dunning School, 80–81.

3 William Archibald Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction and Related Topics, (New York: Macmillan, 1897) 8, 13, 24, 178.

4 Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction and Related Topics, 176–77, 190-191, 252.

William Archibald Dunning. Photography credit to American Historical Association

William Archibald Dunning. Photography credit to American Historical Association

Georgia Scarlett, puppy of Dunning School scholar C. Mildred Thompson, was named for the heroine in Gone With the Wind. Photography credit to University of Georgia Archives Special Collections

Georgia Scarlett, puppy of Dunning School scholar C. Mildred Thompson, was named for the heroine in Gone With the Wind. Photography credit to University of Georgia Archives Special Collections

We know that Margaret Mitchell read and internalized the works of the Dunning School. She was a particularly big fan of C. Mildred Thompson, who was also from Georgia and who was the only female member of the Dunning School. Thompson wrote to Mitchell to tell her how much she enjoyed Gone With the Wind—enough to name her new puppy after Scarlett O’Hara—and Mitchell wrote her back. Thompson’s book, Reconstruction in Georgia, was, Mitchell said, her “mainstay” and “comfort” as she wrote Gone With the Wind.5 Thompson sent Mitchell a copy of Reconstruction in Georgia, after she heard what trouble Mitchell had finding one while researching GWTW. Mitchell also owned other Dunning School histories of Reconstruction, including Claude Bowers’ The Tragic Era: Reconstruction After Lincoln. Bowers’ book was a bit different from Thompson’s. He wasn’t writing for an academic audience; he was writing for the public. In his book, he took the most dramatic and least substantiated claims of the Dunningites and repackaged them for a mass audience.

Margaret Mitchell’s letters and her bookshelf indicate that she owned and read these books. But the evidence for her use of Thompson, Bowers, and others’ works doesn’t stop there. GWTW also clearly reflects them. Mitchell pulled closely from both Bowers and Thompson, weaving their ideas into her storytelling in GWTW.

5 Mitchell, “Feb. 9 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to C. Mildred Thompson”; Thompson, University of Georgia Special Collections, Margaret Mitchell Papers, MS 905, Box 84, Folder 33, “Sept. 7 Letter from C. Mildred Thomspon To Margaret Mitchell”; Thompson, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, C. Mildred Thompson Papers, MSS 256, Box 1, Folder 7, “Undated Letter from C. Mildred Thompson to Margaret Mitchell”; Thompson, University of Georgia Special Collections, Margaret Mitchell Papers, MS 905, Box 84, Folder 33.

Fooled by the Freedman's Bureau? Attempts to Explain Freedpeople's Politics

Gone With the Wind

“Formerly their white masters had given the orders. Now they had a new set of masters, the Bureau and the Carpetbaggers, and their orders were: ‘You’re just as good as any white man, so act that way. Just as soon as you can vote the Republican ticket, you are going to have the white man’s property! It’s as good as yours now. Take it, if you can get it!”

The Tragic Era

“The freedmen clung to the illusion planted in their minds by demagogues that the economic status of the races was to be reversed by the distribution of the land among them. This cruelly false hope was being fed by private soldiers, Bureau agents, and low Northern whites circulating among the negroes on terms of social equality in the cultivation of their prospective votes.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“The bad repute of the Freedman’s Bureau was due more directly to the political activities of its agents in 1867 and 1868, when they manipulated the helpless black voters for their own aggrandizement.”

Negative Portrayals of Black Voters and the Freedman's Bureau

Gone With the Wind

“Formerly their white masters had given the orders. Now they had a new set of masters, the Bureau and the Carpetbaggers, and their orders were: ‘You’re just as good as any white man, so act that way. Just as soon as you can vote the Republican ticket, you are going to have the white man’s property! It’s as good as yours now. Take it, if you can get it!”

The Tragic Era

“The freedmen clung to the illusion planted in their minds by demagogues that the economic status of the races was to be reversed by the distribution of the land among them. This cruelly false hope was being fed by private soldiers, Bureau agents, and low Northern whites circulating among the negroes on terms of social equality in the cultivation of their prospective votes.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“The bad repute of the Freedman’s Bureau was due more directly to the political activities of its agents in 1867 and 1868, when they manipulated the helpless black voters for their own aggrandizement.”

The idea, echoed in all three of these books, that Black people were being somehow tricked into voting for Republican candidates was a common one in Dunning School interpretations of Reconstruction. It played into the idea that Black people were incapable of political participation without being led by whites, and it served as an outlet for frustrated white southern Democrats attempting to explain why their former slaves wouldn’t vote for Democratic candidates. In reality, many Black people voted for the Republican Party because they realized Republicans were the party interested in advocating for them and their rights. In contrast, the Democratic Party was responsible for passing Black Codes while the party still held power in the South during the early days of Reconstruction in 1865 and 1866. Those codes often reflected the rules and restrictions of slavery.6

6 Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877, (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 110–11.

Gone With the Wind

“This Bureau, organized by the Federal government to take care of the idle and excited ex-slaves, was drawing them from the plantations into the villages and cities by the thousands. The Bureau fed them while they loafed and poisoned their minds against their former owners. Gerald’s old overseer, Jonas Wilkerson, was in charge of the local Bureau, and his assistant was Hilton, Cathleen Calvert’s husband. These two industriously spread the rumor that the Southerners and Democrats were just waiting for a good chance to put the negroes back into slavery and that the negroes’ only hope of escaping this fate was the protection given them by the Bureau and the Republican party. Wilkerson and Hilton furthermore told the negroes they were as good as the whites in every way and soon white and negro marriages would be permitted, soon the estates of their former masters would be divided and every negro would be given forty acres and a mule for his own. They kept the negroes stirred up with tales of cruelty perpetrated by whites and, in a section long famed for the affectionate relations between slaves and slave owners, hate and suspicion began to grow.”

The Tragic Era

“Meanwhile the Southern people were fighting for the preservation of their civilization. The negroes would not work, the plantations could not produce. The freedmen clung to the illusion planted in their minds by demagogues that the economic status of the races was to be reversed by the distribution of the land among them. This cruelly false hope was being fed by private soldiers, Bureau agents, and low Northern whites circulating among the negroes on terms of social equality in the cultivation of their prospective votes.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“Thus, in the summer and fall of 1865, vagabondage was the general condition of the freemen. Plantations suffered from the loss of labor, from their depredations on the crops, while towns were overwhelmed with throngs of idle blacks that crowded everywhere.”

Negative Portrayals of Black Voters and the Freedman's Bureau

Gone With the Wind

“This Bureau, organized by the Federal government to take care of the idle and excited ex-slaves, was drawing them from the plantations into the villages and cities by the thousands. The Bureau fed them while they loafed and poisoned their minds against their former owners. Gerald’s old overseer, Jonas Wilkerson, was in charge of the local Bureau, and his assistant was Hilton, Cathleen Calvert’s husband. These two industriously spread the rumor that the Southerners and Democrats were just waiting for a good chance to put the negroes back into slavery and that the negroes’ only hope of escaping this fate was the protection given them by the Bureau and the Republican party. Wilkerson and Hilton furthermore told the negroes they were as good as the whites in every way and soon white and negro marriages would be permitted, soon the estates of their former masters would be divided and every negro would be given forty acres and a mule for his own. They kept the negroes stirred up with tales of cruelty perpetrated by whites and, in a section long famed for the affectionate relations between slaves and slave owners, hate and suspicion began to grow.”

The Tragic Era

“Meanwhile the Southern people were fighting for the preservation of their civilization. The negroes would not work, the plantations could not produce. The freedmen clung to the illusion planted in their minds by demagogues that the economic status of the races was to be reversed by the distribution of the land among them. This cruelly false hope was being fed by private soldiers, Bureau agents, and low Northern whites circulating among the negroes on terms of social equality in the cultivation of their prospective votes.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“Thus, in the summer and fall of 1865, vagabondage was the general condition of the freemen. Plantations suffered from the loss of labor, from their depredations on the crops, while towns were overwhelmed with throngs of idle blacks that crowded everywhere.”

These quotes provide another example of the same false Dunning School arguments about the Freedmen’s Bureau and the recently emancipated. Jonas Wilkerson was a Freedmen’s Bureau agent in Gone With the Wind, and Hilton was a stereotypical “low [class] northern white.” Their roles in the novel demonstrate the influence of narratives such as Bowers’ in The Tragic Era on Margaret Mitchell.

Justifying the Ku Klux Klan: Blending Romanticism and Historical Inaccuracies

Gone With the Wind

“The very suspicion of seditious utterances against the government, suspected complicity in the Ku Klux Klan, or complaint by a negro that a white man had been uppity to him were enough to land a citizen in jail. Proof and evidence were not needed. The accusation was sufficient. And thanks to the incitement of the Freedmen’s Bureau, negroes could always be found who were willing to bring accusations.”

Gone With the Wind

“But far above their anger at the waste and mismanagement and graft was the resentment of the people at the bad light in which the governor represented them in the North. When Georgia howled against corruption, the governor hastily went North, appeared before Congress and told of white outrages against negroes, of Georgia’s preparation for another rebellion and the need for a stern military rule in the state. No Georgian wanted trouble with the negroes and they tried to avoid trouble. No one wanted another war, no one wanted or needed bayonet rule. All Georgia wanted was to be let alone so the state could recuperate. But with the operation of what came to be known as the governor’s ‘slander mill,’ the North saw only a rebellious state that needed a heavy hand, and a heavy hand was laid upon it.”

The Tragic Era

“Soon the carpetbag politicians began bombarding the Northern press with stories of outrages. It was charged, and believed, that these occasionally organized bogus Klans to commit crimes to the end that Federal bayonets could be had to sustain their rotten regimes in the stricken States. Cases there were, where men unable to give the password in the real Klan were stripped in Tennessee and found to be followers of [William G. “Parson”] Brownlow [Tennessee governor who sided with the Radical Republicans]. But it is indubitably true that the ignorant among poor whites, who hated the negroes, crowded in, took possession in many places, and wrought deadly damage.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“As we have seen, anti-[Georgia Governor Rufus] Bullock men, controlling both houses of the legislature, refused Bullock’s demand to declare members ineligible. The legislature rejected Bullock’s favorites for U.S. Senate, and expelled negro members from both houses. But most serious of all, Democratic electors were chosen in the presidential election in November. The circumstances, together with Ku Klux outrages, real and fictitious, were made much of by Governor Bullock in convincing his friends in Washington that the state which he had administered for six months as governor was not a state, but a military district, ‘with no adequate protection for life and property.’

Reconstruction in Georgia

“The second scheme of the reconstructionists, fathered by Governor Bullock and sponsored in Congress by B.F. [Benjamin] Butler, was to prolong the power of the Radicals in Georgia by postponing the election of a new assembly, due by law in December, 1870. The wheels of the scandal mill continued to grind, not slowly like the mills of the gods, but with all speed, and members of Congress were plied with accounts of dreadful happenings in Georgia.”

Pro-Klan Arguments

Gone With the Wind

“The very suspicion of seditious utterances against the government, suspected complicity in the Ku Klux Klan, or complaint by a negro that a white man had been uppity to him were enough to land a citizen in jail. Proof and evidence were not needed. The accusation was sufficient. And thanks to the incitement of the Freedmen’s Bureau, negroes could always be found who were willing to bring accusations.”

“But far above their anger at the waste and mismanagement and graft was the resentment of the people at the bad light in which the governor represented them in the North. When Georgia howled against corruption, the governor hastily went North, appeared before Congress and told of white outrages against negroes, of Georgia’s preparation for another rebellion and the need for a stern military rule in the state. No Georgian wanted trouble with the negroes and they tried to avoid trouble. No one wanted another war, no one wanted or needed bayonet rule. All Georgia wanted was to be let alone so the state could recuperate. But with the operation of what came to be known as the governor’s ‘slander mill,’ the North saw only a rebellious state that needed a heavy hand, and a heavy hand was laid upon it.”

The Tragic Era

“Soon the carpetbag politicians began bombarding the Northern press with stories of outrages. It was charged, and believed, that these occasionally organized bogus Klans to commit crimes to the end that Federal bayonets could be had to sustain their rotten regimes in the stricken States. Cases there were, where men unable to give the password in the real Klan were stripped in Tennessee and found to be followers of [William G. “Parson”] Brownlow [Tennessee governor who sided with the Radical Republicans]. But it is indubitably true that the ignorant among poor whites, who hated the negroes, crowded in, took possession in many places, and wrought deadly damage.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“As we have seen, anti-[Georgia Governor Rufus] Bullock men, controlling both houses of the legislature, refused Bullock’s demand to declare members ineligible. The legislature rejected Bullock’s favorites for U.S. Senate, and expelled negro members from both houses. But most serious of all, Democratic electors were chosen in the presidential election in November. The circumstances, together with Ku Klux outrages, real and fictitious, were made much of by Governor Bullock in convincing his friends in Washington that the state which he had administered for six months as governor was not a state, but a military district, ‘with no adequate protection for life and property.’

“The second scheme of the reconstructionists, fathered by Governor Bullock and sponsored in Congress by B.F. [Benjamin] Butler, was to prolong the power of the Radicals in Georgia by postponing the election of a new assembly, due by law in December, 1870. The wheels of the scandal mill continued to grind, not slowly like the mills of the gods, but with all speed, and members of Congress were plied with accounts of dreadful happenings in Georgia.”

The idea that the crimes committed by the Ku Klux Klan across the South during Reconstruction were manufactured was used both to protect Klan members and to discredit Republican politicians in the South.7 Many of the “outrages” Georgia’s Governor Bullock brought to Congress, presented in all three of these books as false, really did take place. Governor Bullock was, in fact, chased out of Georgia after the December 1870 elections by the Ku Klux Klan, not because he was corrupt, but because he supported Republican politics and (to an extent) the political rights of Black men.8

7 Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 434.

8 “Rufus Bullock”, The New Georgia Encyclopedia, accessed February 27, 2024, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/rufus-bullock-1834-1907/.

Melodrama and Reconstruction: Exaggerations to Justify Jim Crow

Gone With the Wind

“Here was the astonishing spectacle of half a nation attempting, at the point of a bayonet, to force upon the other half the rule of negroes, many of them scarcely one generation out of the African jungles. The vote must be given to them but it must be denied to most of their former owners.”

The Tragic Era

“Thus, too, the brilliant and colorful leaders and spokesmen on the South are given their proper place in the dramatic struggle for the preservation of Southern civilization and the redemption of their people. I have sought to re-create the black and bloody drama of these years, to show the leaders of the fighting factions at close range, to picture the moving masses, both whites and blacks, in North and South, surging crazily under the influence of the poisonous propaganda on which they were fed.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“On one side was law and on the other was the social custom of generations. Ideally, it may have been a human and civilizing act to protect the weaker race with the power of the ballot; but practically, when enfranchisement was conferred against the will of the white people and contrary to their profound sense of right and fitness, the new power left the freedmen with but little more actual freedom in 1872 than they enjoyed in 1866.”

Negative Portrayals of Reconstruction Politics

Gone With the Wind

“Here was the astonishing spectacle of half a nation attempting, at the point of a bayonet, to force upon the other half the rule of negroes, many of them scarcely one generation out of the African jungles. The vote must be given to them but it must be denied to most of their former owners.”

The Tragic Era

“Thus, too, the brilliant and colorful leaders and spokesmen on the South are given their proper place in the dramatic struggle for the preservation of Southern civilization and the redemption of their people. I have sought to re-create the black and bloody drama of these years, to show the leaders of the fighting factions at close range, to picture the moving masses, both whites and blacks, in North and South, surging crazily under the influence of the poisonous propaganda on which they were fed.”

Reconstruction in Georgia

“On one side was law and on the other was the social custom of generations. Ideally, it may have been a human and civilizing act to protect the weaker race with the power of the ballot; but practically, when enfranchisement was conferred against the will of the white people and contrary to their profound sense of right and fitness, the new power left the freedmen with but little more actual freedom in 1872 than they enjoyed in 1866.”

o All three of these passages demonstrate the melodrama with which Reconstruction was portrayed by the Dunning School. In particular, these passages highlight the way that white southerners were portrayed as Reconstruction’s victims, fighting against brutal and unfair conditions. This is contrary to many modern interpretations of Reconstruction, which highlight the short time that white southerners who had just fought a war against the United States government were prevented from participating in that government and the enormous amount of work that was needed to even begin to bring Black southerners to a position of social and political equality with their white counterparts.9

9 Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877.

Splitting From the Source Material: Margaret Mitchell's Editorial Choices

Interestingly, though we know how much Margaret Mitchell respected C. Mildred Thompson and her work, there are several moments in Gone With the Wind that Mitchell chooses Bowers’ more melodramatic, less accurate interpretation in The Tragic Era over Thompson’s. For example:

Gone With the Wind

“But these ignominies and dangers were as nothing compared with the peril of white women, many bereft by the war of male protection, who lived alone in the outlying districts and on lonely roads. It was the large number of outrages on women and the ever-present fear for the safety of their wives and daughters that drove Southern men to cold and trembling fury and caused the Ku Klux Klan to spring up overnight. And it was against this nocturnal organization that the newspapers of the North cried out most loudly, never realizing the tragic necessity that brought it into being. The North wanted every member of the Ku Klux hunted down and hanged, because they had dared take the punishment of crime into their own hands at a time when the ordinary processes of law and order had been overthrown by the invaders.”

The Tragic Era

“All over the South white women armed themselves in self-defense. Before the Klan appeared, and after the Loyal Leagues had spread their poison, no respectable white woman dared venture out in the black belt unprotected. […] It was not until the original Klan began to ride that white women felt some sense of security.”

“Rape is the foul daughter of Reconstruction.”

Gone With the Wind

“Now they had not only the Bureau agitators and the Carpetbaggers urging them on, but the incitement of whisky as well, and outrages were inevitable. Neither life nor property was safe from them and the white people, unprotected by law, were terrorized. Men were insulted on the streets by drunken blacks, houses and barns were burned at night, horses and cattle and chickens stolen in broad daylight, crimes of all varieties were committed and few of the perpetrators were brought to justice.”

The Tragic Era

“But always, with these newly freed negroes armed and in easy reach of liquor, the shadow of an awful fear rested upon the women of the communities where they were stationed.”

Gone With the Wind

“But these ignominies and dangers were as nothing compared with the peril of white women, many bereft by the war of male protection, who lived alone in the outlying districts and on lonely roads. It was the large number of outrages on women and the ever-present fear for the safety of their wives and daughters that drove Southern men to cold and trembling fury and caused the Ku Klux Klan to spring up overnight. And it was against this nocturnal organization that the newspapers of the North cried out most loudly, never realizing the tragic necessity that brought it into being. The North wanted every member of the Ku Klux hunted down and hanged, because they had dared take the punishment of crime into their own hands at a time when the ordinary processes of law and order had been overthrown by the invaders.”

“Now they had not only the Bureau agitators and the Carpetbaggers urging them on, but the incitement of whisky as well, and outrages were inevitable. Neither life nor property was safe from them and the white people, unprotected by law, were terrorized. Men were insulted on the streets by drunken blacks, houses and barns were burned at night, horses and cattle and chickens stolen in broad daylight, crimes of all varieties were committed and few of the perpetrators were brought to justice.”

The Tragic Era

“All over the South white women armed themselves in self-defense. Before the Klan appeared, and after the Loyal Leagues had spread their poison, no respectable white woman dared venture out in the black belt unprotected. […] It was not until the original Klan began to ride that white women felt some sense of security.”

“Rape is the foul daughter of Reconstruction.”

“But always, with these newly freed negroes armed and in easy reach of liquor, the shadow of an awful fear rested upon the women of the communities where they were stationed.”

o The version of the Ku Klux Klan presented by Mitchell and Bowers in this passage was designed to provoke sympathy for Klan members, and to justify the violence they carried out over the course of Reconstruction. It particularly misrepresents the reason the Ku Klux Klan was formed. White women rarely faced sexual violence from Black men and the Klan did not form to defend them, because there was nothing to defend. Rather, it formed to intimidate Black people who attempted to practice their newly obtained civil and political rights, typically through extrajudicial violence that led historians to characterize the Klan as a terrorist group.

o Though she showed sympathy for the Klan in line with her biased opinions about Black people, C. Mildred Thompson was aware of this fact, and clearly stated it in Reconstruction in Georgia.

“The chief motive assigned for the attacks on negroes was ‘to control them’, to ‘keep them down’. More than one case appeared where negroes were driven off when they seemed to be prospering too well in a neighborhood of poor, thriftless whites. What was termed ‘impudence’ to white people was a frequent cause of discipline upon the blacks, described thus: ‘If there is any dispute about a settlement or anything of that sort, it is not expected that a colored man will contend, in a white man’s face, for anything as a white man would. Any language that he would regard as not offensive at all from a white man would be impudence from a negro.’ Or again: ‘It is considered impudence for a negro not to be polite to a white man—not to pull off his hat and bow and scrape to a white man, as was always done formerly.’”

It’s unclear what exactly motivated Mitchell to rely on Bowers over Thompson. Perhaps she used Bowers’ version of the Klan for dramatic effect, something she does discuss in letters to her publisher, Harold Latham of Macmillan, or perhaps Bowers’ work aligned better with the myths and misperceptions she’d grown up with.10 For example, Mitchell‘s favorite book as a teenager was Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, which inspired The Birth of a Nation, a movie that was sympathetic enough to the Ku Klux Klan that it inspired the organization’s rebirth in the early twentieth century.11

10 Mitchell, “July 27, 1935 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Harold Latham,” New York Public Library Archives, Macmillan Company Records, MssCol 1830, Box 95, Microfilm Reel 1.

11 Mitchell, “Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Thomas Dixon,” August 15, 1938, University of Georgia Special Collections, Margaret Mitchell Papers, MS 905, Box 21, Folder 89; Mitchell, “Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Thomas Dixon,” October 3, 1938, University of Georgia Special Collections, Margaret Mitchell Papers, MS 905, Box 21, Folder 89.

W.E.B. Du Bois. Photography credit to James E. Purdy, 1907

W.E.B. Du Bois. Photography credit to James E. Purdy, 1907

Contradicting the Dunning School

The prominence of the Dunning School, and the fact that they were published by a respected institution like Columbia University might make it seem as if Margaret Mitchell didn’t have much choice when it came to what kind of information she could get about the Civil War and Reconstruction. This is true to some extent. Her environment was very limited compared to ours, but that doesn’t mean she couldn’t access contradictory ideas.

Just three miles away from the Atlanta apartment where she wrote GWTW, nationally prominent Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois was writing his own book, Black Reconstruction in America. Du Bois published Black Reconstruction in 1935, the same year Mitchell gave her manuscript to the Macmillan Publishing Company. In Black Reconstruction, Du Bois argued that Reconstruction hadn’t been a total failure. He pointed out that most former Confederate states kept their Reconstruction-era constitutions, virtually unchanged from their original forms, and that Reconstruction was responsible for the establishment of valued programs such as public schools and hospitals in the South. When Reconstruction did fail, Du Bois wrote, it wasn’t because of the incapabilities of Black people. Rather, it was because prewar white elites did not want to lose the power they had held over Black people during slavery and were willing to use violence to regain that power. These white elites also wanted to ensure that the formerly enslaved couldn’t exercise the rights they had gained during Reconstruction.

Though he presented his research other historians, including William A. Dunning at conferences for decades, and published articles about it in The Atlantic and other prominent magazines, Du Bois’ work wasn’t accepted by the white academic mainstream until the 1960s. More moderate historians felt he was “taking sides” against white southerners in his work.12 Others felt a bit more strongly. In response, Thomas Dixon, author of The Clansman and one of Margaret Mitchell’s literary idols, wrote a book in which Du Bois was the central villain.

Today, DuBois’ work still forms the basis of most historians’ interpretations of Reconstruction. He tried to approach Reconstruction from the lens that “the Negro in America and in general is an average and ordinary human being, who under a given environment develops like human beings.”13 His approach that is now much more respected than Dunning’s assumption of Black Americans’ inherent inferiority.

12 Herbert Aptheker, The Literary Legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois, (New York, White Plains: Kraus International Publications, 1989), 225–33.

13 Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America; an Essay toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880.

There’s no evidence that Margaret Mitchell ever read W.E.B. Du Bois’ work or that she would have had any desire to, even if she was aware of who he was and what he stood for. Even if she had wanted to, it was published too late for her to incorporate it into Gone With the Wind. Du Bois’ work was not the only place, however, that Mitchell could get access to critiques of her Dunning School interpretation of Reconstruction.

Shortly after Mitchell submitted the manuscript that became Gone With the Wind to Macmillan Publishing Company, Macmillan sent it to a test reader, Professor Charles Everett, who taught English at Columbia University. Professor Everett’s general assessment of Gone With the Wind was glowing. He thought it was an excellent novel that would sell many copies. But he did have concerns. For example, the thought, “the author should keep out her own feelings in one or two places where she talks about negro rule.”

Margaret Mitchell. Photography credit to Atlanta History Center

Margaret Mitchell. Photography credit to Atlanta History Center

Mitchell responded to Everett’s critique, writing, “He is absolutely right in that matter and I thank him for calling my attention to it. […] I have tried to keep out venom, bias, bitterness as much as possible. All the V, B&B in the book were to come through the eyes and head and tongues of the characters, as reactions from what they saw and heard and felt.”14 Her response to Everett is interesting for two reasons. First, it hints she was aware that her portrayal of Black people during Reconstruction was biased or bitter, which are fundamental flaws of the Dunning School works she relied on. Second, Mitchell implies she is planning to change this content. The published version of Gone With the Wind includes many long passages in which the book’s omniscient narrator delivers significant pieces of information about Reconstruction that echo the Dunning School and its biases. It would seem that Mitchell either chose not to edit her Reconstruction passages, or that they were originally much more problematic.

Both Charles Everett’s critique and W.E.B. Du Bois’ book indicate something very important to bear in mind about Margaret Mitchell’s world when it comes to her responsibility for the historical content of Gone With the Wind. Mitchell and Du Bois were so close to one another physically when their books were published and yet, because Du Bois was part of Atlanta’s Black community, and Mitchell was part of its white community, their conceptions of the same historical event were completely different. Segregation hadn’t only changed the ways they went shopping or navigated public transit. It had also impacted the way they thought. The key difference was that Du Bois couldn’t ignore the Dunning School in his study of history. Mitchell and the Dunning School though, could easily ignore him.

Everett, as a white professor who taught at the same university as Dunning had, was a bit different. Mitchell saw his opinions as worth considering, but was not disturbed by his concerns about her portrayal of Reconstruction. They were minor critiques she found easy enough to respond to briefly or completely ignore. They did not upset her conception of her book as being historically accurate. To her, they were matters of opinion, rather than fact. This reveals the very different way that Reconstruction was understood in the early twentieth century and helps to explain the ways that the Dunning School pervaded not just in Gone With the Wind, but in American culture.

14 Mitchell, “July 27, 1935 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Harold Latham," NYPL.